(Important sections of the Indian nuclear liability bill 2010)

http://www.idsa.in/system/files/ib_CivilNuclearLiabilityBill.pdf (Bill with comments)

http://www.dianuke.org/rules-the-civil-liability-for-nuclear-damage-bill-2010/ (Rules under the Act)

http://radscihealth.org/rsh/realism/RealismApp1a-attch.pdf (Consequences of reactor accidents)http://www.idsa.in/system/files/ib_CivilNuclearLiabilityBill.pdf (Bill with comments)

http://www.dianuke.org/rules-the-civil-liability-for-nuclear-damage-bill-2010/ (Rules under the Act)

http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/article475974.ece (Is life cheap in India)

http://www.indianexpress.com/news/a-guide-to-indias-civil-liability-for-nuclear-damage-bill-2010/661979/ (Implications of the nuclear liability bill)

http://www.clraindia.org/include/CLRA%20Nuke%20Bill%20policy%20brief.pdfhttp://www.indianexpress.com/news/a-guide-to-indias-civil-liability-for-nuclear-damage-bill-2010/661979/ (Implications of the nuclear liability bill)

http://airwebworld.com/articles/index.php?article=1529

http://lawmin.nic.in/ld/regionallanguages

http://lawmin.nic.in/ld/regionallanguages/THE%20CIVIL%20LIABILITY%20OF%20NUCLEAR%20DAMAGE%20ACT,2010.%20%2838%20OF2010%29.pdf (CIVIL LIABILITY ACT)

http://www.npcil.nic.in/pdf/Civil_Nucler_Liability.pdf (RULES)

http://toxicswatch.blogspot.in/2011/11/governments-rules-on-nuclear-liability.html

(comments on Rules)

Price-Anderson Act

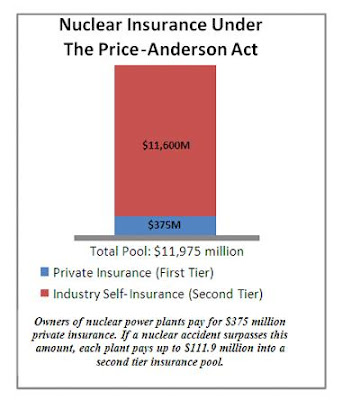

The Price-Anderson Act, which became law on September 2, 1957, was designed to ensure that adequate funds would be available to satisfy liability claims of members of the public for personal injury and property damage in the event of a nuclear accident involving a commercial nuclear power plant. The legislation helped encourage private investment in commercial nuclear power by placing a cap, or ceiling on the total amount of liability each holder of a nuclear power plant licensee faced in the event of an accident. Over the years, the "limit of liability" for a nuclear accident has increased the insurance pool to more than $12 billion.

Under existing policy, owners of nuclear power plants pay a premium each year for $375 million in private insurance for offsite liability coverage for each reactor unit. This primary or first tier, insurance is supplemented by a second tier. In the event a nuclear accident, causes damages in excess of $375 million, each licensee would be assessed a prorated share of the excess up to $111.9 million. With 104 reactors currently licensed to operate, this secondary tier of funds contains about $11.6 billion. If 15 percent of these funds are expended, prioritization of the remaining amount would be left to a federal district court. If the second tier is depleted, Congress is committed to determine whether additional disaster relief is required.

The only insurance pool writing nuclear insurance, American Nuclear Insurers, is comprised of property-casualty insurance companies. About 13 percent of the pool's total liability capacity comes from foreign sources. The average annual premium for a single-unit reactor site is $830,000. The premium for a second or third reactor at the same site is discounted to reflect a sharing of limits.

Claims resulting from nuclear accidents are covered under Price-Anderson; for that reason, all property and liability insurance policies issued in the U.S. exclude nuclear accidents. Claims can include any incident (including those that come about because of theft or sabotage) in the course of transporting nuclear fuel to a reactor site; in the storage of nuclear fuel or waste at a site; in the operation of a reactor, including the discharge of radioactive effluent; and in the transportation of irradiated nuclear fuel and nuclear waste from the reactor.

Price-Anderson does not require coverage for spent fuel or nuclear waste stored at interim storage facilities, transportation of nuclear fuel or waste that is not either to or from a nuclear reactor, or acts of theft or sabotage occurring after planned transportation has ended.

Insurance under Price-Anderson covers bodily injury, sickness, disease or resulting death, property damage and loss as well as reasonable living expenses for individuals evacuated. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 extended the Price-Anderson Act to December 31, 2025.

Price-Anderson in Action

When the accident at Three Mile Island Nuclear Power Plant in Middletown, Pa., occurred in 1979, the Price-Anderson Act provided liability insurance to the public. Coverage was available to those in need by the time Pennsylvania’s governor recommended the evacuation of pregnant women and families with young children who lived near the plant. At the time of the accident, private insurers had $140 million of coverage available in the first tier pools. Insurance adjusters advanced money to evacuated families in order to cover their living expenses, only requesting that unused funds be returned; recipients responded by sending back several thousand dollars. The insurance pools also reimbursed over 600 individuals and families for wages lost as a result of the accident.

In addition to the immediate concerns, the insurance pools were later used to settle a class-action suit for economic loss filed on behalf of residents who lived near Three Mile Island. Because the Price-Anderson Act allowed for a certain amount of money to be spent on each accident, it covered court fees as well. The last of the litigation surrounding the accident was resolved in 2003.

To date, the insurance pools have paid approximately $71 million in claims and litigation costs associated with the Three Mile Island accident.

Disaster Relief Funds-Stafford Act

Disaster relief is also available to State and local governments under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act if a nuclear accident is declared an emergency or major disaster by the President. The Act is designed to provide early assistance to accident victims. Under a cost-sharing provision, State governments pay 25 percent of the cost of temporary housing for up to 18 months, home repair, temporary mortgage or rental payments and other "unmet needs" of disaster victims; the federal government pays the balance.

NOTE: Private Insurance (First Tier) industry pays $375M + each industry gets $11,600 M out of cooperative pool in the Second Tier. So totally each accident pays $11,600+$375 = $11,975M as compensation. To replenish the common pool 104 reactors pay $112M , totaling pool of $12 billion (common fund)

Liability for Nuclear Damage

- Operators of nuclear power plants are liable for any damage caused by them, regardless of fault. They therefore normally take out insurance for third-party liability, and in most countries they are required to do so.

- The potential cross boundary consequences of a nuclear accident require an international nuclear liability regime, so national laws are supplemented by a number of international conventions.

- Liability is limited by both international conventions and by national legislation, so that beyond the limit (normally covered by insurance) the state can accept responsibility as insurer of last resort, as in all other aspects of industrial society.

An illustrative exchange on insuring nuclear power plants It is commonly asserted that nuclear power stations are not covered by insurance, and that insurance companies don't want to know about them either for first-party insurance of the plant itself or third-party liability for accidents. This is incorrect, and the misconception was addressed as follows in 2006 by a broker who had been responsible for a nuclear insurance pool: "it is wrong [to believe] that insurers will not touch nuclear power stations. In fact, wherever they are available to private sector insurers, Western-designed nuclear installations are sought-after business because of their high engineering and risk management standards. This has been the case for fifty years." He elaborated: "My comment refers very much to the world scene and is not contentious. Apart from Three Mile Island, the claim experience has been very good. Chernobyl was not insured. Significantly, because Chernobyl was of a design that would not have been an acceptable risk at the time, notably the lack of a containment structure, the accident had no impact on premium rates for Western plants. |

The structure of insurance of nuclear installations is different from ordinary industrial risks. Insurance (direct damage and third party liability insurance) is placed with either one of the many national insurance pools which brings together insurance capacity for nuclear risks from the domestic insurers in the local country, or into one of the mutual insurance associations such as Nuclear Electric Insurance Limited (NEIL) based in USA or EMANI and ELINI based in Europe. These are set up by the nuclear industry itself. Third Party liability involves international conventions, national legislation channeling liability to the operators, and pooling of insurance capacity in more than twenty countries. The national nuclear insurance pool approach was particularly developed in the UK in 1956 as a way of marshalling insurance capacity for the possibility of serious accidents. Other national pools that followed were modeled on the UK pool - now known as Nuclear Risk Insurers Limited, and based in London. The mutualisation of insurance risks began with the forerunner of NEIL in 1973

Ever since the first commercial nuclear power reactors were built, there has been concern about the possible effects of a severe nuclear accident, coupled with the question of who would be liable for third-party consequences. This concern was based on the supposition that even with reactor designs licensable in the West, a cooling failure causing the core to melt would result in major consequences akin to those of the Chernobyl disaster. It was supposed that damage caused could be extensive, creating the need for compulsory third party insurance schemes for nuclear operators, and international conventions to deal with transboundary damage. On the other hand it was realized that nuclear power makes a valuable contribution to meeting the world’s energy demands and that in order for it to continue doing so, individual operator liability had to be curtailed and beyond a certain level, risk had to be socialized. Experience over five decades has shown the fear of catastrophe to be exaggerated, though the local impact of a severe accident or terrorist attack was shown at Fukushima in 2011 to be considerable, even with minor direct human casualties. Prior to that, the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 was taken as being indicative.

Nuclear liability principles

Most conventions and laws regarding nuclear third party liability have at their heart the following principles:

- Strict liability of the nuclear operator

- Exclusive liability of the operator of a nuclear installation

- Compensation without discrimination based on nationality, domicile or residence

- Mandatory financial coverage of the operator's liability

- Exclusive jurisdiction (only courts of the State in which the nuclear accident occurs have jurisdiction)

- Limitation of liability in amount and in time

Strict liability means that the victim is relieved from proving fault. In the case of an accident the operator (power plant, enrichment/fuel facility, reprocessing facility) is liable whether or not any fault or negligence can be proven. This simplifies the litigation process, removing any obstacles, especially such as might exist with the burden of proof, given the complexity of nuclear science. In layman’s terms: strict liability means a claimant does not need to prove how an accident occurred.

Exclusive liability of the operator means that in the case of an accident, all claims are to be brought against the nuclear operator. This legal channeling is regardless of the accident's cause. By inference suppliers or builders of the plant are protected from public litigation in the case of an accident. Again this simplifies the process because claimants do not have to figure out who is responsible – under law it will be the nuclear operator.

Mandatory financial coverage means that the operator must maintain insurance cover, and it ensures that funds will be made available by the operator or their insurers to pay for damages. The minimum amount of protection required is set by national laws which in turn often depend on international treaty obligations. Over time the amount of this mandatory protection has increased, partially adjusting for inflation and partially allowing for an increased burden of responsibility to be passed on to nuclear operators.

Exclusive jurisdiction means that only the courts of the country in which the accident occurs has jurisdiction over damages claims. This has two effects; firstly it prevents what is known as jurisdiction shopping, whereby claimants try and find courts and national legislation more friendly to their claims, thus offering nuclear operators a degree of certainty and protection. Secondly it locates the competent court close to the source of damage meaning that victims do not have to travel far in order to lodge claims. This combined with exclusive liability ensures that relevant courts are accessible, even when the accident is transport-related and the relevant company based far away.

Limitation of liability protects individual nuclear operators and thus is often controversial. By limiting the amount that operators would have to pay, the risks of an accident are effectively socialized. Beyond a certain level of damage, responsibility is passed from the individual operator either on to the State or a mutual collective of nuclear operators, or indeed both. In essence this limitation recognizes the benefits of nuclear power and the tacit acceptance of the risks a State takes by permitting power plant construction and operation, as with other major infrastructure.

Altogether these principles ensure that in the case of an accident, meaningful levels of compensation are available with a minimal level of litigation and difficulty.

Exclusive liability of the operator means that in the case of an accident, all claims are to be brought against the nuclear operator. This legal channeling is regardless of the accident's cause. By inference suppliers or builders of the plant are protected from public litigation in the case of an accident. Again this simplifies the process because claimants do not have to figure out who is responsible – under law it will be the nuclear operator.

Mandatory financial coverage means that the operator must maintain insurance cover, and it ensures that funds will be made available by the operator or their insurers to pay for damages. The minimum amount of protection required is set by national laws which in turn often depend on international treaty obligations. Over time the amount of this mandatory protection has increased, partially adjusting for inflation and partially allowing for an increased burden of responsibility to be passed on to nuclear operators.

Exclusive jurisdiction means that only the courts of the country in which the accident occurs has jurisdiction over damages claims. This has two effects; firstly it prevents what is known as jurisdiction shopping, whereby claimants try and find courts and national legislation more friendly to their claims, thus offering nuclear operators a degree of certainty and protection. Secondly it locates the competent court close to the source of damage meaning that victims do not have to travel far in order to lodge claims. This combined with exclusive liability ensures that relevant courts are accessible, even when the accident is transport-related and the relevant company based far away.

Limitation of liability protects individual nuclear operators and thus is often controversial. By limiting the amount that operators would have to pay, the risks of an accident are effectively socialized. Beyond a certain level of damage, responsibility is passed from the individual operator either on to the State or a mutual collective of nuclear operators, or indeed both. In essence this limitation recognizes the benefits of nuclear power and the tacit acceptance of the risks a State takes by permitting power plant construction and operation, as with other major infrastructure.

Altogether these principles ensure that in the case of an accident, meaningful levels of compensation are available with a minimal level of litigation and difficulty.

International Framework

Governments have long recognized the risk of a nuclear accident causing transboundary damage. This led to the development of international frameworks to ensure that access to justice was readily available for victims outside of the country in which an accident occurs, so far as the countries are party to the relevant conventions. The number of different international instruments and their arrangements often give rise to confusion. Many of the major instruments, outlined below, have been amended several times and not all countries party to the earlier version have ratified the latter. The result is a patchwork quilt of countries and conventions and work towards harmonization of these regimes is ongoing.

Before 1997, the international liability regime was embodied primarily in two instruments:

- the IAEA's Vienna Convention* on Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage of 1963 (entered into force in 1977), and

- the OECD's Paris Convention on Third Party Liability in the Field of Nuclear Energy of 1960 which entered into force in 1968 and was bolstered by the Brussels Supplementary Convention in 1963**.

- the IAEA's Vienna Convention* on Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage of 1963 (entered into force in 1977), and

- the OECD's Paris Convention on Third Party Liability in the Field of Nuclear Energy of 1960 which entered into force in 1968 and was bolstered by the Brussels Supplementary Convention in 1963**.

* Parties to Vienna Convention are mainly outside of Western Europe, including: Argentina, Bulgaria, Czech Rep, Egypt, Hungary, Lithuania, Mexico, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Ukraine. See also http://www.iaea.org/Publications/Documents/Conventions/liability_status.pdf

** The Paris convention includes all Western European countries except Ireland, Austria, Luxembourg and Switzerland. Parties to both Paris & Brussels are: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, UK. Paris only: Greece, Portugal, Turkey. See also: http://www.nea.fr/html/law/paris-convention-ratification.html

http://www.nea.fr/html/law/brussels-convention-ratification.html

** The Paris convention includes all Western European countries except Ireland, Austria, Luxembourg and Switzerland. Parties to both Paris & Brussels are: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, UK. Paris only: Greece, Portugal, Turkey. See also: http://www.nea.fr/html/law/paris-convention-ratification.html

http://www.nea.fr/html/law/brussels-convention-ratification.html

These Conventions were linked by the Joint Protocol adopted in 1988 (see below) to bring together the geographical scope of the two*. They are based on the concept of civil law and adhere to the principles outlined above. Specifically they include the following provisions:

- Liability is channeled exclusively to the operators of the nuclear installations (legal channelling means exclusive liability of operator, and protects suppliers);

- Liability of the operator is absolute, i.e. the operator is held liable irrespective of fault, except for "acts of armed conflict, hostilities, civil war or insurrection";

- Liability of the operator is limited in amount. Under the Vienna Convention the upper ceiling for operator liability is not fixed**; but it may be limited by legislation in each State. The lower limit may not be less than US$ 5 million. Under the 1960 Paris convention, liability is limited to not more than 15 million Special Drawing Rights*** (SDRs - about US$ 23 million) and not less than SDR 5 million.

- Liability is limited in time. Generally, compensation rights are extinguished under both Conventions if an action is not brought within ten years. Additionally, States may not limit the operator’s liability to less than two years under the 1960 Paris convention, or three years under 1960 Vienna convention, from the time when the damage is discovered.

- The operator must maintain insurance or other financial security for an amount corresponding to his liability or the limit set by the Installation State, beyond this level the Installation State can provide public funds but can also have recourse to the operator;

- Jurisdiction over actions lies exclusively with the courts of the Contracting Party in whose territory the nuclear incident occurred;

- Non-discrimination of victims on the grounds of nationality, domicile or residence.

- Definition of nuclear damage covers property, health and loss of life but does not make provision for environmental damage, preventative measures and economic loss. This greatly reduces the total number of possible claimants, but increases the level of compensation available to the remainder.

* parties: http://www.iaea.org/Publications/Documents/Conventions/jointprot_status.pdf** The Paris Convention set a maximum liability of 15 million Special Drawing Rights - SDR (about EUR 18 million), but this was increased under the Brussels Supplementary Convention up to a total of 300 million SDRs (about EUR 360 million), including contributions by the installation State up to SDR 175 million (EUR 210M) and other Parties to the Convention collectively on the basis of their installed nuclear capacity for the balance.

***An SDR is the unit of currency of the international monetary fund, it is approximately equal to 1.5 US dollars.

The 1963 Brussels supplementary convention created a system of three tiers to provide for damages. Parties of the Brussels convention must also be party to the Paris convention which provides for the first tier of funds via the nuclear operator’s liability. Tier two requires the state to pay the difference between the operator’s liability (which is set under national law) and SDR 70 million. Tier three calls upon all parties to the convention to supply up to SDR 50 million. The maximum total amount available for compensation of the 1963 convention is therfore SDR 120 million, though note that this has since been increased - see below..

Following the Chernobyl accident in 1986, the IAEA initiated work on all aspects of nuclear liability with a view to improving the basic Conventions and establishing a comprehensive liability regime. In 1988, as a result of joint efforts by the IAEA and OECD/NEA, the Joint Protocol Relating to the Application of the Vienna Convention and the Paris Convention was adopted. Parties to the Joint protocol are treated as if they are Parties to both conventions. If an accident takes place in a country bound by the Paris convention which causes damages in a country bound by the Vienna convention, then victims in the latter are subject to compensation as per the Paris convention. The reverse is also true. Generally, no country can be a party to both conventions because the exact details are not consistent, leading to potential conflict in their simultaneous application. The Joint protocol was also intended to obviate any possible conflicts of law in the case of international transport of nuclear material. It entered into force in 1992.

The Vienna convention has been amended once in 1997, while the Paris convention and associated Brussels convention have been amended three times; in 1964, 1982 and 2004, though the latest amendment has not yet been ratified by enough countries to pass into force.

In 1997 governments took a significant step forward in improving the liability regime for nuclear damage when delegates from over 80 States adopted a Protocol to Amend the Vienna Convention. The amended IAEA Vienna Convention sets the possible limit of the operator's liability at not less than 300 million SDRs (about EUR 360 million) and entered into force in 2003 but with few members. It also broadens the definition of nuclear damage (to include the concept of environmental damage and preventive measures), extends the geographical scope of the Convention, and extends the period during which claims may be brought for loss of life and personal injury. It also provides for jurisdiction of coastal states over actions incurring nuclear damage during transport.

There was no change in the liability caps provided for under either of the 1964 Paris or Brussels amendments or the 1982 Paris amendment. However, under the 1982 Brussels amendment, the second tier of finance (made available by the country in which the accident occurs) was raised to the difference between the operator’s liability and SDR 175 million (i.e. between SDR 160 million and 170 million ), while the third tier called upon all contracting countries to contribute up to SDR125 million so that the total amount currently available is SDR 300 million.

In 2004, contracting parties to the OECD Paris (and Brussels) Conventions signed Amending Protocols which brought the Paris Convention more into line with the IAEA Conventions amended or adopted in 1997. The principal objective of the amendments was to provide more compensation to more people for a wider scope of nuclear damage. They also shifted more of the onus for insurance on to industry. Consequently new limits of liability were set as follows: Operators (insured) €700 million, Installation State (public funds) €500 million, Collective state contribution (Brussels) €300 million => total €1500 M. The definition of "nuclear damage" is broadened to include environmental damage and economic costs, and the scope of application is widened. Moreover the 2004 amendment removed the requirement for a state to restrict the maximum liability of a nuclear operator, allowing for the first time states with a policy preference for unlimited liability to join the convention.

These Paris/ Brussels amendments are expected to be ratified by the contracting parties once they have consulted with industry stakeholders and then drafted the necessary amending legislation. They are not yet in force, and the old limits still apply (c €210 million, €360 million).

Also in 1997 IAEA parties adopted a Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC)*. This defines additional amounts to be provided through contributions by States Parties collectively on the basis of installed nuclear capacity and a UN rate of assessment, basically at 300 SDRs per MW thermal (ie about EUR 360 million total). The CSC - not yet in force - is an instrument to which all States may adhere regardless of whether they are parties to any existing nuclear liability conventions or have nuclear installations on their territories, , though in the case where they are not party to either Paris or Vienna they must still implement national laws consistent with an annex to the CSC. In order to pass into force the CSC must be ratified by five countries with a minimum of 400 GW thermal of installed nuclear capacity. Currently the only ratifying party with significant nuclear generating capacity is the USA (c 300 GWt). Fourteen countries have signed it, now including India, but most have not yet ratified it. The CSC is set to enter into force on the 90th day after date of ratification by at least five States who have a minimum of 400,000 units of installed nuclear capacity (ie MWt). India will bring about 22 GWt operating and under construction.

Table 1: Nuclear power States and liability conventions they are party to

Countries | Conventions party to | Countries | Conventions party to | |

Argentina | VC; RVC; CSC | Lithuania | VC; JP | |

Armenia | VC; | Mexico | VC | |

Belgium | PC; BSC; RPC; RBSC | Netherlands | PC; BSC; JP; RPC; RBSC | |

Brazil | VC | Pakistan | ||

Bulgaria | VC; JP | Romania | VC; JP; RVC; CSC | |

Canada | Russia | VC | ||

China | Slovak Republic | VC; JP | ||

Czech Republic | VC; JP | Slovenia | PC; BSC; JP; RPC; RBSC | |

Finland | PC; BSC; JP; RPC; RBSC | South Africa | ||

France | PC; BSC; RPC; RBSC | Spain | PC; BSC; RPC; RBSC | |

Germany | PC; BSC; JP; RPC; RBSC | Sweden | PC; BSC; JP; RPC; RBSC | |

Hungary | VC; JP | Switzerland | PC; RPC; BSC; RBSC | |

India | CSC* | Taiwan | ||

Iran | Ukraine | VC; JP | ||

Japan | United Kingdom | PC; BSC; RPC; RBSC | ||

Korea | United States | CSC |

PC = Paris Convention (PC). RPC = 2004 Revised Paris Protocol. Not yet in force

BSC = Brussels Supplementary Convention. RBSC = 2004 Revised Brussels Supplementary Convention. Not yet in force

VC = Vienna Convention. RVC = Revised Vienna Convention

JP = 1988 Joint Protocol.

CSC = Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC). Not yet in force.

* India has signed the CSC but has not yet ratified it, and it is not yet clear whether their domestic liability law conforms with the requirements of the convention.

BSC = Brussels Supplementary Convention. RBSC = 2004 Revised Brussels Supplementary Convention. Not yet in force

VC = Vienna Convention. RVC = Revised Vienna Convention

JP = 1988 Joint Protocol.

CSC = Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC). Not yet in force.

* India has signed the CSC but has not yet ratified it, and it is not yet clear whether their domestic liability law conforms with the requirements of the convention.

Beyond the provision of the above-mentioned instruments there is at least a tacit acceptance that the installation state will make available funds to cover anything in excess of these provisions, just as is the case with any major disaster - natural or other (the main industiral ones have been chemical plants). This has long been accepted in all developed countries. In the event of government payout to meet immediate claims however, the operator's liability is in no way extinguished, and taxpayers would expect to recover much or all of the sums involved.

However, several states with a significant current or planned nuclear capacity such as Japan, China and India, are not yet party to any international nuclear liability convention, so far relying on their own arrangements.

Beyond the international conventions, most countries with commercial nuclear programs also have their own legislative regimes for nuclear liability. These national regimes implement the conventions’ principles, and impose financial security requirements which vary from country to country. There are three categories of countries in this regard: those that are party to one or both of the international conventions and have their own legislation, those that are not parties to an international convention but have their own legislation (notably USA, Canada, Japan, S.Korea), and those that are not party to a convention and are without their own legislation (notably China).

In 2010 both France's CEA and the IAEA called for an overhaul and rationalization of the several international conventions. In particular, the Paris Convention open only to OECD countries was unsatisfactory when reactor vendors and utilities from those countries were building plants in non-OECD countries. Partly due to the US channeling situation described below, the CSC is seen as a possible basis for an all-encompassing international regime

US Framework

The USA takes a somewhat different approach, and having pioneered the concept is not party to any international nuclear liability convention, except for the CSC, which has yet to come into force. The Price Anderson Act - the world's first comprehensive nuclear liability law - has since 1957 been central to addressing the question of liability for nuclear accident. It now provides $12.5 billion in cover without cost to the public or government and without fault needing to be proven. It covers power reactors, research reactors, enrichment plants, waste repositories and all other nuclear facilities.

It was renewed for 20 years in mid 2005, with strong bipartisan support, and requires individual operators to be responsible for two layers of insurance cover. The first layer is where each nuclear site is required to purchase US$ 375 million liability cover (as of 2011) which is provided by a private insurance pool, American Nuclear Insurers (ANI). This is financial liability, not legal liability as in European liability conventions.

The second layer or secondary financial protection (SFP) program is jointly provided by all US reactor operators. It is funded through retrospective payments if required of up to $112 million per reactor per acident* collected in annual instalments of $17.5 million (and adjusted with inflation). Combined, the total provision comes to over $12.2 billion paid for by the utilities. (The Department of Energy also provides $10 billion for its nuclear activities.) Beyond this cover and irrespective of fault, Congress, as insurer of last resort, must decide how compensation is provided in the event of a major accident.

* plus up to 5% if required for legal costs.

More than $150 million has been paid by US insurance pools in claims and costs of litigation since the Price- Anderson Act came into effect, all of it by the insurance pools. Of this amount, some $71 million related to litigation following the 1979 accident at Three Mile Island.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) requires all licensees for nuclear power plants to show proof that they have the primary and secondary insurance coverage mandated by the Price-Anderson Act. Licensees obtain their primary insurance for third-party liability through American Nuclear Insurers (ANI), and ANI manages the secondary insurance program also. Licensees also sign an agreement with NRC to keep the insurance in effect. American Nuclear Insurers also has a contractual agreement with each of the licensees to collect the retrospective premiums if these payments become necessary. A certified copy of this agreement, which is called a bond for payment of retrospective premiums, is provided to NRC as proof of secondary insurance. It obligates the licensee to pay the retrospective premiums to ANI if required.

American Nuclear Insurers is a pool comprised of some 60 investor-owned stock insurance companies, including the major ones. About half the pool's total liability capacity comes from foreign sources such as Lloyd's of London. The average annual premium for a single-unit reactor site is $400,000. The premium for a second or third reactor at the same site is discounted to reflect a sharing of limits.

The nuclear operators' mutual arrangement for insuring the actual plants against accidents is Nuclear Electric Insurance Limited (NEIL) which is well funded (a $5 billion surplus) and cooperates closely with the American Nuclear Insurers pool. It was founded in 1980 and insures operators for any costs associated with property damage, decontamination, extended outages and related nuclear risks. For property damage and on-site decontamination, up to $2.75 billion is available to each commercial reactor site. The policies provide coverage for direct physical damage to, or destruction of, the insured property as a result of an accident [“accident” is defined as a sudden and fortuitous event, an event of the moment, which happens by chance, is unexpected and unforeseeable. Accident does not include any condition which develops, progresses or changes over time, or which is inevitable]. The policies prioritize payment of expenses to stabilize the reactor to a safe condition and decontaminate the plant site.

The Price Anderson Act has been represented as a subsidy to the US nuclear industry. If considered thus, the value of the subsidy is the difference between the premium for full coverage and the premium for $10 billion in coverage. On the basis of data obtained from two studies - one conducted by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and the other by the Department of Energy (DOE) - the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the subsidy probably amounts to less than 1 percent of the levelized cost for new nuclear capacity.

The Price Anderson Act does not fully align with international conventions in that legal channelling is forbidden by state laws, so the Act allows only economic channelling, whereby the operator is economically liable but other entities may be held legally liable. This is a complication regarding any future universal compensation regime, though a provision was written into the CSC to allow the USA to join despite this situation. Hence the CSC may prove the most realistic basis for any universal third party regime.

Japan

Japan is not party to any international liability convention but its law generally conforms to them. Two laws governing them are revised about every ten years: the Law on Compensation for Nuclear Damage and Law on Contract for Liability Insurance for Nuclear Damage.

Plant operator liability is exclusive and absolute, and power plant operators must provide a financial security amount of JPY 120 billion (US$ 1.4 billion) - half that to 2010. The government may relieve the operator of liability if it determines that damage results from “a grave natural disaster of an exceptional character”, and in any case liability is unlimited.

For the Fukushima accident in 2011 the government set up a new state-backed institution to expedite payments to those affected. The body is to receive financial contributions from electric power companies with nuclear power plants in Japan, and from the government through special bonds that can be cashed whenever necessary. The government bonds total JPY 5 trillion ($62 billion). The new institution will include representatives from other nuclear generators and will also operate as an insurer for the industry, being responsible to have plans in place for any future nuclear accidents. The provision for contributions from other nuclear operators is similar to that in the USA. The government estimates that Tepco will be able to complete its repayments in 10 to 13 years, after which it will revert to a fully private company with no government involvement. Meanwhile it will pay an annual fee for the government support, maintain adequate power supplies and ensure plant safety.

In relation to the 1999 Tokai-mura fuel plant criticality accident, insurance covered JPY 1 billion and the parent company (Sumitomo) paid the balance of JPY 13.5 billion.

Other countries

In the UK, the Energy Act 1983 brought legislation into line with earlier revisions to the Paris/Brussels Conventions and set a new limit of liability for particular installations. In 1994 this limit was increased again to £140 million for each major installation, so that the operator is liable for claims up to this amount and must insure accordingly. The majority of this insurance is provided by a pool of UK insurers comprising 8 insurance companies and 16 Lloyds syndicates - - Nuclear Risk Insurers. Beyond £140 million, the current Paris/Brussels system applies, with government contribution to SDR 300 million (c €360 million). The government is proposing legislation which would require operators' insurance of EUR 1.2 billion. The level would initially be set at EUR 700 million specified under the 2004 Paris/Brussels Protocol (when it enters force) and then increased by EUR 100 million annually. Also, proposals allow for the government to provide waivers, indemnity, and government-provided insurance to nuclear operators in cases where commercial insurance or other financial security measures are unavailable in the private market. A public consultation on this is under way until the end of April 2011.

In mainland Europe, individual countries have legislation in line with the international conventions and where set, cap levels vary. Germany has unlimited operator liability and requires €2.5 billion security which must be provided by the operator for each plant. This security is partly covered by insurance, to €256 million. France requires financial security of EUR 91 million per plant. Switzerland (which has signed but not yet ratified the international conventions) requires operators to insure to €600 million. It is proposed to increase this to €1.1 billion and ratify the Paris and Brussels conventions.

Finland has ratified the 2004 Joint Protocol relating to Paris and Vienna conventions and in anticipation of this coming into force it passed a 2005 Act which requires operators to take at least € 700 million insurance cover. Currently the level is only EUR 300 million. Also operator liability is to be unlimited beyond the € 1.5 billion provided under the Brussels Convention. "Nuclear damage" is as defined in revised Paris Convention, and includes that from terrorism.

Sweden has also ratified the 2004 Joint Protocol relating to Paris and Vienna conventions. The country's Nuclear Liability Act requires operators to be insured for at least SEK 3300 million (EUR 345 million), beyond which the state will cover to SEK 6 billion per incident. However, Sweden is reviewing how this relates to the EUR 700 million operator's liability under the Joint Protocol amending the Paris convention, and has announced that it will seek unlimited operator liability.

The Czech Republic is moving towards ratifying the amendment to the Vienna Convention and in 2009 increased the mandatory minimum insurance cover required for each reactor to CZK 8 billion (EUR 296 million).

In Europe there are two mutual insurance arrangements which supplement commercial insurance pool cover for operators of nuclear plants. The European Mutual Association for the Nuclear Industry (EMANI) was founded in 1978 and European Liability Insurance for the Nuclear Industry (ELINI) created in 2002. ELINI plans to make EUR 100 million available as third party cover, and its 28 members have contributed half that to late 2007 for a special capital fund. ELINI's members comprise most EU nuclear plant operators. EMANI has some 70 members and covers over 100 sites, mostly in Europe. Its funds are about EUR500 million.

In Canada the Nuclear Liability and Compensation Act is also in line with the international conventions and establishes the licensee's absolute and exclusive liability for third party damage. Suppliers of goods and services are given an absolute discharge of liability. The limit of C$75 million per power plant set in 1976 as the insurance cover required for individual licensees was increased to $650 million in the Act's 2008 revision, though this has not yet passed. Cover is provided by a pool of insurers, and claimants need not establish fault on anyone's part, but must show injury. Beyond the cap level, any further funds would be provided by the government.

Russia is party to the Vienna Convention since 2005 and has a domestic nuclear insurance pool comprising 23 insurance companies covering liability of some $350 million. It has a reinsurance arrangement with Ukraine and is setting one up with China. It has some "interim" bilateral agreements to cover entities working under safety assistance programs, but the legislative deficit here is a deterrent to Western contractors in particular..

Ukraine adopted a domestic liability law in 1995 and has revised it since in order to harmonise with the Vienna Convention, which it joined in 1996. It is also party to the Joint Protocol and has signed the CSC. Operator liability is capped at 150 million SDRs (c €180 million). Special provisions provisions apply to work on the Chernobyl shelter so as to extend coverage outside the Vienna Convention countries.

China is not party to any international liability convention but is an active member of the international insurance pooling system, which covers both first party risks and third party liability once fuel is loaded into a reactor. China's 1986 interim domestic law on nuclear liability issued by the State Council contains most of the elements of the international conventions and the liability limit was increased to near international levels in September 2007. It is also setting up a reinsurance arrangement with Russia which is more symbol than substance.

(For insurance of the plants themselves, Hong Kong-listed Ping'an Insurance Company accounts for more than half of China's nuclear power insurance market, with its clients including nuclear power plants in Guangdong, Jiangsu and both first- and second-phase projects of Qinshan Nuclear Power Station in Zhejiang. Four Chinese Insurance companies provided US$ 1.85 billion worth of insurance to Tianwan Nuclear Power Station in Jiangsu, most of which will be reinsured internationally. About RMB 40 billion ($5.85 billion) insurance for the first two EPR units of the Taishan nuclear plant in being provided by Ping'an, All Trust, CPIC, PICC and others. In late 2009 seven insurance companies and China Power Investment Corporation (CPI) signed a RMB 100 billion insurance cooperation agreement with China Guangdong Nuclear Power Co to insure the ten CPR-1000 units that CGNPC plans to build in the next three years. In December 2007 Ningde Nuclear Power had announced a US$2 billion insurance agreement with Ping An Insurance Corp for its 4-unit CPR-1000 nuclear power project in Fujian Province. All this is first party cover only.)

The Indian government has introduced a bill which will bring the country's nuclear liability provisions broadly into line internationally, making operators liable for any nuclear accident, and protecting third party suppliers. Operators need to take out insurance up to the liability cap of $110 million, and other provisions are related to the IAEA's Vienna Convention (1997 amendment).

No comments:

Post a Comment